Preface:

Before we get into the nitty gritty of this post (which is highly detailed). We figured we would explain catatonia from a high level. Catatonia can largely be reduced to an imbalance in Glutamate:GABA ratio. In one way or another there is more Glutamate relative to GABA or less GABA relative to Glutamate. We know that GABA is inhibitory & Glutamate is excitatory. So what happens in catatonia is the brain is metaphorically on fire with an overwhelming amount of excitation. This is true regardless of specific catatonic presentation. This underlying pathology explains why benzodiazepines work so well. That is, they boost GABA & help to restore the proper Glutamate:GABA ratio, thus calming the brain. It is quite interesting to watch a patient recover from a stuporous catatonic state after receiving a benzodiazepine.

One other interesting tidbit, is the autonomic obedience that is present in catatonic patients. A patient may appear conscious & simply nonverbal by choice. But, when asked to hold both hands over their head they will immediately do it & will continue to do it, until you tell them to relax.

Skip to the bottom to read the patient scenarios!

And of course the disclaimer:

DISCLAIMER

The content provided in this Substack post is for entertainment and informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical advice. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the writer and should not be taken as definitive or authoritative. Readers should not rely solely on the information provided in this post to make decisions about patient care. Instead, use this content as a starting point for further research and consult a qualified healthcare professional before making any changes to treatment or medication regimens.

I. Introduction

A. Brief overview of catatonia

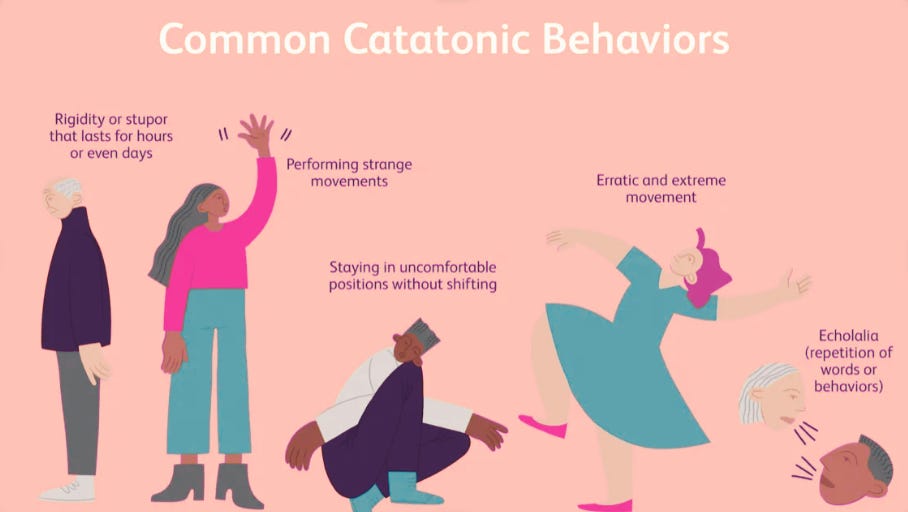

Catatonia is a complex neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by a broad range of motor, behavioral, and emotional symptoms. It presents as a cluster of signs and symptoms that can manifest in various forms, such as immobility, rigidity, mutism, negativism, or extreme agitation. Though initially described by Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum in 1874 as a distinct disorder, catatonia is now understood to be a symptom associated with a wide range of psychiatric and medical conditions. It is crucial for psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioners (PMHNPs) to recognize and address catatonia effectively, as it can have severe consequences if left untreated.

B. Importance of understanding catatonia for PMHNPs

As a PMHNP, understanding catatonia is essential due to its clinical relevance and potential impact on patients' lives. Timely identification and appropriate treatment can significantly improve outcomes and reduce morbidity and mortality associated with catatonia. Additionally, given the varied nature of catatonia, PMHNPs must be equipped with the knowledge to differentiate it from other disorders that present with similar features.

C. Goals of the article

This article aims to provide PMHNPs with a comprehensive understanding of catatonia, its occurrence along a spectrum, and the various approaches to treatment. It will also offer insights into the associated psychiatric and medical conditions, diagnostic criteria, and the importance of early recognition and intervention. The goal is to equip PMHNPs with the necessary knowledge to identify and manage catatonia effectively in their practice.

Part II. Understanding Catatonia

A. Definition and historical context

Catatonia is a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by a diverse range of motor, behavioral, and emotional symptoms. These symptoms can manifest as psychomotor disturbances, such as stupor, catalepsy, waxy flexibility, posturing, rigidity, negativism, or stereotypies. Alternatively, they may present as excessive motor activity, impulsivity, or even aggression. The term "catatonia" was first introduced by German psychiatrist Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum in 1874, who initially described it as a distinct progressive disorder characterized by motor symptoms and cognitive decline.

Over time, the understanding of catatonia has evolved. It is now recognized as a symptom rather than a standalone disorder. Catatonia is often associated with various psychiatric and medical conditions, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, neurodevelopmental disorders, and autoimmune encephalitis. Although the exact cause of catatonia remains unknown, it is believed to involve multiple neurotransmitter systems, particularly gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate, which play a crucial role in motor and behavioral regulation.

B. Catatonia as a symptom, not a standalone disorder

As our understanding of catatonia has evolved over the years, it is now widely accepted that catatonia is a symptom rather than a standalone disorder. This shift in perspective has significantly impacted the diagnostic and treatment approaches for catatonia. Instead of being classified as a separate illness, catatonia is now considered a psychomotor symptom that can be present across a range of psychiatric and medical conditions.

Recognizing catatonia as a symptom rather than an independent disorder is crucial for PMHNPs as it highlights the importance of investigating underlying causes when a patient presents with catatonic features. Rather than focusing solely on the management of catatonic symptoms, PMHNPs should consider the possibility of associated psychiatric or medical conditions, which may require additional evaluation and treatment. This approach not only ensures that the root cause of catatonia is addressed but also helps prevent misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment.

The identification of catatonia as a symptom has also led to changes in diagnostic classification systems. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), catatonia is no longer a subtype of schizophrenia. Instead, it is recognized as a specifier that can be applied to various disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and other medical conditions. This change underscores the importance of understanding catatonia as a cross-cutting symptom and emphasizes the need for PMHNPs to be vigilant in recognizing and managing it across various clinical settings.

C. Associated psychiatric and medical conditions

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a chronic and severe mental disorder characterized by disturbances in thought, perception, and behavior. Catatonia can occur in individuals with schizophrenia, manifesting as psychomotor symptoms that may complicate the clinical presentation. While catatonia was once considered a subtype of schizophrenia, the DSM-5 now classifies it as a specifier that can be applied to the disorder.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder characterized by episodes of mania, hypomania, and depression. Catatonia can present during both manic and depressive episodes, complicating the diagnosis and management of bipolar disorder. It is essential for PMHNPs to recognize catatonia in the context of bipolar disorder and to treat it promptly, as untreated catatonia can result in severe complications and poor outcomes.

Major depressive disorder

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mental health condition characterized by persistent low mood, anhedonia, and a range of cognitive and physical symptoms. Catatonia can occur in severe cases of MDD, often referred to as "catatonic depression." In such cases, catatonic features may include immobility, mutism, negativism, or other motor symptoms, which can significantly impact the patient's functioning and quality of life.

Neurodevelopmental disorders

Neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), may also present with catatonic features. Catatonia in the context of ASD is sometimes referred to as "autistic catatonia" and can manifest as a sudden or gradual decline in motor, social, and communication skills. PMHNPs should be aware of the possibility of catatonia in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders and monitor for any changes in functioning that may indicate the onset of catatonic symptoms.

Autoimmune encephalitis

Autoimmune encephalitis is a group of inflammatory brain disorders caused by the immune system mistakenly attacking healthy brain tissue. Catatonia can be a presenting feature of autoimmune encephalitis, particularly in cases of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Early recognition and treatment of catatonia in this context are crucial, as prompt immunotherapy can significantly improve patient outcomes.

Others

Other medical conditions that can be associated with catatonia include metabolic disorders (e.g., hepatic encephalopathy), neurologic conditions (e.g., traumatic brain injury), infections (e.g., encephalitis, meningitis), and substance-induced states (e.g., drug withdrawal, intoxication). PMHNPs should maintain a high index of suspicion for catatonia in patients with diverse medical backgrounds and consider thorough medical evaluation to identify any underlying conditions that may contribute to the catatonic presentation.

III. Catatonia Spectrum

A. Stuporous catatonia

Symptoms

Stuporous catatonia, also known as "retarded" or "hypoactive" catatonia, is characterized by a marked decrease in motor activity and responsiveness. Symptoms of stuporous catatonia may include:

Stupor: A state of reduced consciousness or unresponsiveness to external stimuli.

Mutism: Little or no verbal communication.

Catalepsy: Maintaining rigid, fixed postures for extended periods.

Waxy flexibility: Minimal resistance to passive movement by another person, allowing limbs to be moved into new positions that are maintained.

Posturing: Holding unusual, often uncomfortable positions for extended periods.

Negativism: A resistance to attempts to change position or behavior, or a lack of response to external stimuli.

Automatic obedience: Following simple commands in a robot-like manner.

Clinical presentation

Patients with stuporous catatonia often present with decreased motor activity, little or no speech, and apparent unresponsiveness to their surroundings. They may maintain unusual postures or exhibit waxy flexibility, appearing almost statue-like. In some cases, patients may display negativism or automatic obedience, complicating the clinical picture.

The presentation of stuporous catatonia can be challenging to differentiate from other conditions, such as severe depression, neurologic disorders, or conversion disorder. It is essential for PMHNPs to consider the possibility of stuporous catatonia in patients presenting with these features, especially in the context of known psychiatric or medical conditions associated with catatonia. Timely identification and appropriate treatment of stuporous catatonia can prevent further complications and improve patient outcomes.

B. Excited catatonia

Symptoms

Excited catatonia, also known as "hyperactive" or "agitated" catatonia, is characterized by an increase in motor activity, impulsivity, and, in some cases, aggression. Symptoms of excited catatonia may include:

Purposeless agitation: Excessive motor activity without an apparent goal or purpose.

Stereotypies: Repetitive, non-goal-directed movements, such as hand wringing, rocking, or pacing.

Echolalia: Repetition of words or phrases spoken by others.

Echopraxia: Mimicking the movements or actions of others.

Impulsivity: Acting on sudden urges or without forethought.

Verbigeration: Meaningless repetition of words or phrases.

Combativeness or aggression: Hostile or violent behavior towards oneself or others.

Clinical presentation

Patients with excited catatonia often present with excessive, purposeless motor activity and may exhibit repetitive or mimicking behaviors. They may be impulsive, engaging in risky or dangerous actions, and, in some cases, display aggression or combativeness towards themselves or others.

The clinical presentation of excited catatonia can be challenging to manage due to the risk of self-harm or harm to others. Additionally, it can be difficult to differentiate from other conditions, such as manic episodes, acute psychosis, or substance-induced agitation. PMHNPs should consider the possibility of excited catatonia in patients presenting with these features, especially in the context of known psychiatric or medical conditions associated with catatonia. Early identification and appropriate treatment of excited catatonia are crucial to prevent further complications and ensure patient safety.

C. Malignant catatonia

Symptoms

Malignant catatonia, also known as "lethal" or "neuroleptic malignant syndrome-like" catatonia, is a severe and potentially life-threatening form of catatonia. Symptoms of malignant catatonia may include:

Fever: Elevated body temperature, often above 100.4°F (38°C).

Autonomic instability: Fluctuations in blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and/or body temperature.

Rigidity: Stiffness or inflexibility of the muscles.

Delirium: Acute confusion, disorientation, or fluctuating levels of consciousness.

Tachycardia: Rapid heart rate.

Tachypnea: Rapid breathing.

Diaphoresis: Excessive sweating.

Dysphagia: Difficulty swallowing.

Clinical presentation

Patients with malignant catatonia often present with a rapid onset of fever, autonomic instability, rigidity, and altered mental status. They may also exhibit other symptoms, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis, and dysphagia. Malignant catatonia can be difficult to differentiate from other life-threatening conditions, such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), malignant hyperthermia, or serotonin syndrome.

Risk of life-threatening complications

Malignant catatonia carries a significant risk of life-threatening complications if not recognized and treated promptly. Complications may include:

Rhabdomyolysis: Breakdown of muscle tissue, which can lead to acute kidney injury or renal failure.

Dehydration and electrolyte imbalances: Due to fever, diaphoresis, and decreased fluid intake.

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: Due to immobility and muscle rigidity.

Aspiration pneumonia: Resulting from dysphagia or an impaired level of consciousness.

Cardiovascular collapse: Due to severe autonomic instability.

Early identification and aggressive treatment of malignant catatonia are crucial to prevent these complications and improve patient outcomes. PMHNPs must maintain a high index of suspicion for malignant catatonia in patients presenting with a combination of fever, rigidity, and altered mental status, especially in the context of known psychiatric or medical conditions associated with catatonia.

IV. Diagnosis of Catatonia

A. DSM-5 criteria

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) provides diagnostic criteria for catatonia. According to the DSM-5, the diagnosis of catatonia requires the presence of three or more of the following 12 symptoms:

Stupor: Decreased or lack of motor activity and responsiveness to external stimuli.

Catalepsy: Maintaining rigid, fixed postures for extended periods.

Waxy flexibility: Minimal resistance to passive movement by another person, allowing limbs to be moved into new positions that are maintained.

Mutism: Little or no verbal communication.

Negativism: Resistance to attempts to change position or behavior, or a lack of response to external stimuli.

Posturing: Holding unusual, often uncomfortable positions for extended periods.

Mannerisms: Odd, exaggerated, or caricatured behaviors.

Stereotypies: Repetitive, non-goal-directed movements, such as hand wringing, rocking, or pacing.

Agitation: Excessive motor activity without an apparent goal or purpose.

Grimacing: Contorted facial expressions.

Echolalia: Repetition of words or phrases spoken by others.

Echopraxia: Mimicking the movements or actions of others.

It is essential for PMHNPs to consider the presence of these symptoms in the context of associated psychiatric or medical conditions to accurately diagnose catatonia.

B. The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale

The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) is a widely used diagnostic tool for assessing the presence and severity of catatonic symptoms. The BFCRS consists of 23 items that cover various catatonic features, such as stupor, mutism, negativism, posturing, and agitation, among others.

Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (absent) to 3 (severe), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 69. A higher score indicates a greater severity of catatonic symptoms. The BFCRS can be used to track the progress of catatonia over time and to monitor the response to treatment.

In addition to the DSM-5 criteria, PMHNPs can use the BFCRS as a valuable tool to aid in the diagnosis of catatonia, assess the severity of symptoms, and guide treatment decisions.

C. Differential diagnosis

When diagnosing catatonia, it is essential for PMHNPs to consider other conditions that may present with similar symptoms. A thorough evaluation and differential diagnosis can help rule out alternative explanations for the observed clinical presentation. Some conditions that may mimic catatonia include:

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, and postural instability. While some of these motor symptoms may overlap with catatonia, Parkinson's disease typically presents with additional clinical features, such as resting tremor and a progressive course, that help differentiate it from catatonia.

Non-epileptic seizures

Non-epileptic seizures, also known as psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), can present with various motor, sensory, or behavioral symptoms that may resemble catatonia. However, PNES usually has a different pattern of presentation and often occurs in the context of psychological stress or trauma. Video-electroencephalogram (video-EEG) monitoring can help differentiate non-epileptic seizures from catatonia by capturing seizure-like events and analyzing the corresponding brain activity.

Conversion disorder

Conversion disorder, also known as functional neurological symptom disorder, involves neurological symptoms such as weakness, paralysis, or abnormal movements that cannot be explained by a medical condition. Conversion disorder can present with motor symptoms that resemble catatonia, making differentiation challenging. However, a careful evaluation of the clinical presentation and the presence of specific psychological stressors or triggers can help distinguish conversion disorder from catatonia.

Others

Several other conditions can present with symptoms that may mimic catatonia, such as:

Encephalitis: Inflammatory brain disorders may present with altered mental status and motor symptoms that can resemble catatonia.

Delirium: Acute confusion, disorientation, and fluctuating levels of consciousness can mimic some features of catatonia.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: This rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disorder can present with cognitive decline, motor symptoms, and psychiatric features that may overlap with catatonia.

Drug-induced movement disorders: Medications, particularly antipsychotics, can cause movement disorders such as akathisia, dystonia, or tardive dyskinesia, which may present with motor symptoms similar to catatonia.

PMHNPs should conduct a thorough assessment and consider these differential diagnoses when evaluating patients presenting with catatonic features. This process will help ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment for the underlying condition.

D. Importance of Early Recognition

Early recognition of catatonia is crucial for several reasons:

Prompt treatment: Identifying catatonia in its early stages allows for the initiation of appropriate treatment, such as benzodiazepines or ECT, as soon as possible. Early intervention can lead to faster symptom resolution and improved patient outcomes.

Prevention of complications: Early recognition and treatment of catatonia can help prevent the development of severe complications, such as malnutrition, dehydration, muscle breakdown, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, which can be life-threatening if left untreated.

Accurate diagnosis: Recognizing catatonia early enables PMHNPs to differentiate it from other conditions with similar presentations, such as Parkinson's disease, non-epileptic seizures, or conversion disorder. An accurate diagnosis is essential for guiding appropriate treatment and managing any underlying psychiatric or medical conditions associated with catatonia.

Reduced morbidity and mortality: Early recognition and treatment of catatonia, especially malignant catatonia, can significantly reduce morbidity and mortality rates. Malignant catatonia, in particular, is associated with a high risk of life-threatening complications, and timely intervention is crucial to prevent poor outcomes.

Improved patient quality of life: Identifying and treating catatonia early can help improve patients' quality of life by alleviating distressing symptoms, such as immobility, mutism, and agitation. This can lead to better overall functioning and a faster return to daily activities and social interactions.

PMHNPs play a vital role in the early recognition of catatonia by maintaining a high index of suspicion for the condition, especially in patients with known risk factors or associated psychiatric and medical conditions. Through early identification and intervention, PMHNPs can significantly impact patient outcomes and contribute to the effective management of catatonia.

V. Treatment Approaches

A. Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are often the first-line treatment for catatonia due to their rapid onset of action, efficacy, and relatively low risk of side effects. They work by enhancing the activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter, resulting in reduced motor and psychological symptoms of catatonia.

Lorazepam

Lorazepam is a benzodiazepine commonly used to treat catatonia. It has a rapid onset of action, usually within 15-30 minutes, and a relatively short half-life of 10-20 hours. Lorazepam can be administered orally, intramuscularly (IM), or intravenously (IV).

The initial dose of lorazepam for treating catatonia is typically 1-2 mg given orally or IM, with the dose repeated every 4-6 hours as needed, up to a maximum of 8 mg per day. In some cases, higher doses may be required, but this should be done with caution and under close monitoring.

The majority of patients with catatonia respond positively to lorazepam, with improvement in symptoms often observed within hours of administration. If there is no response or only partial response to lorazepam after 48-72 hours, alternative treatments should be considered.

Diazepam

Diazepam is another benzodiazepine that can be used to treat catatonia, particularly when lorazepam is not available or contraindicated. Diazepam has a longer half-life (20-70 hours) than lorazepam and can be administered orally, IM, or IV.

The initial dose of diazepam for treating catatonia is typically 5-10 mg given orally, IM, or IV, with the dose repeated every 6-8 hours as needed, up to a maximum of 30-40 mg per day. As with lorazepam, higher doses may be required in some cases but should be used cautiously and under close monitoring.

While diazepam is effective in treating catatonia, it may be less preferable than lorazepam due to its longer half-life and potential for accumulation in the body, which can increase the risk of side effects, especially in elderly patients or those with liver dysfunction.

B. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Indications

ECT is a highly effective treatment for catatonia, particularly when patients do not respond to benzodiazepines or have severe, life-threatening symptoms. ECT is also indicated for catatonia associated with mood disorders, such as major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, and in cases where rapid symptom resolution is crucial.

Efficacy

ECT has been shown to be highly effective in treating catatonia, with response rates of 80-90%. Often, patients experience rapid and significant improvement in their symptoms, sometimes after just a few ECT sessions. ECT can be a lifesaving intervention for patients with malignant catatonia or those at risk of severe complications.

Risks and side effects

While ECT is generally safe and effective, it is not without risks and side effects. Potential side effects may include headache, muscle soreness, nausea, confusion, and short-term memory loss. Serious complications are rare but can include cardiovascular events, prolonged seizures, and, in extremely rare cases, death. However, the benefits of ECT often outweigh the risks, particularly in severe cases of catatonia that are unresponsive to other treatments.

C. Other pharmacological treatments

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotic medications may be used as an adjunctive treatment in cases where catatonia is associated with psychotic disorders like schizophrenia. However, antipsychotics should be used with caution, as they can sometimes exacerbate catatonic symptoms or trigger neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a potentially life-threatening condition.

Mood stabilizers

Mood stabilizers, such as lithium or valproate, can be helpful in treating catatonia associated with bipolar disorder. They may be used in combination with benzodiazepines or ECT for optimal results. However, mood stabilizers are generally not effective in treating catatonia when used as a monotherapy.

Antidepressants

Antidepressant medications may be used to treat catatonia associated with major depressive disorder. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can be considered, depending on the specific clinical presentation and patient factors. However, antidepressants are typically not effective in treating catatonia as monotherapy and should be used in conjunction with other treatments like benzodiazepines or ECT.

D. Non-pharmacological interventions

In addition to pharmacological treatments like benzodiazepines and ECT, non-pharmacological interventions can play a crucial role in managing catatonia and addressing associated psychiatric and medical conditions. Some non-pharmacological interventions include:

Supportive psychotherapy

Supportive psychotherapy can help patients with catatonia by providing a safe, non-judgmental space to express their feelings and concerns. It can also help patients develop coping strategies to deal with stressors, improve self-esteem, and foster a sense of hope and resilience. Psychotherapy may be particularly helpful in addressing underlying psychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety, or trauma, that may contribute to catatonia.

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy can be beneficial for patients recovering from catatonia by helping them regain their functional abilities and independence in daily activities. Occupational therapists can work with patients to develop strategies for managing self-care tasks, work or school demands, and social interactions. They can also help patients address any cognitive, sensory, or motor impairments that may have resulted from catatonia or its treatment.

Family education

Educating family members about catatonia, its symptoms, causes, and treatment options is essential for fostering a supportive environment and promoting patient recovery. Family education can help loved ones understand the importance of adherence to treatment, recognize early warning signs of relapse, and learn how to provide practical and emotional support to the patient. Involving family members in the treatment process can also help address any family-related stressors or conflicts that may contribute to the development or exacerbation of catatonia.

By incorporating non-pharmacological interventions into the treatment plan, PMHNPs can provide a comprehensive and holistic approach to managing catatonia, addressing not only the symptoms but also the underlying causes and psychosocial factors that may contribute to the condition.

VI. Case Studies

Case Study 1: Stuporous Catatonia in a Patient with Major Depressive Disorder

A. Illustrate various presentations of catatonia

Ms. Smith, a 45-year-old woman with a history of major depressive disorder, was brought to the emergency room by her family due to sudden onset of mutism, immobility, and refusal to eat or drink. Upon examination, Ms. Smith demonstrated waxy flexibility and posturing, maintaining unusual body positions for extended periods. She also exhibited negativism, resisting attempts to move her limbs, and showed signs of autonomic instability, such as fluctuating blood pressure and heart rate.

B. Demonstrate successful treatment approaches

Ms. Smith was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit, where she was started on a trial of lorazepam 2 mg orally. Within a few hours of the first dose, her catatonic symptoms began to improve. Over the next few days, she was given lorazepam every 6 hours, and her catatonic symptoms continued to improve significantly. Her antidepressant medication was also optimized to better manage her underlying major depressive disorder.

As her catatonic symptoms resolved, Ms. Smith was gradually reintroduced to group therapy and individual supportive psychotherapy, which helped her process the stressors that may have contributed to the development of catatonia. Additionally, she worked with an occupational therapist to regain her functional abilities and independence in daily activities. Her family was educated about catatonia and the importance of treatment adherence, early intervention, and providing a supportive environment for recovery.

C. Highlight the importance of early intervention

Ms. Smith's case highlights the importance of early recognition and intervention in catatonia. Her rapid response to benzodiazepine treatment underscores the effectiveness of this first-line treatment approach in managing catatonic symptoms. The prompt initiation of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, as well as the optimization of her antidepressant regimen, allowed Ms. Smith to recover more quickly and return to her normal daily functioning. This case also emphasizes the value of a comprehensive treatment approach that addresses both catatonia and the underlying psychiatric condition to promote long-term recovery and reduce the risk of relapse.

Case Study 2: Excited Catatonia in a Patient with Schizophrenia

A. Illustrate various presentations of catatonia

Mr. Johnson, a 32-year-old man with a history of schizophrenia, was brought to the emergency room by the police after being found wandering the streets in a highly agitated state. Upon examination, Mr. Johnson exhibited symptoms of excited catatonia, including excessive motor activity, impulsivity, and combativeness. He also demonstrated echolalia, repeating words or phrases spoken by others, and exhibited stereotypy, engaging in repetitive, purposeless movements.

B. Demonstrate successful treatment approaches

Mr. Johnson was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit, where he was started on a trial of lorazepam 2 mg intramuscularly due to his inability to take oral medication. His catatonic symptoms began to improve within a few hours of the first dose. Over the next few days, he received lorazepam every 6 hours, with continued improvement in his catatonic symptoms. His antipsychotic medication was also optimized to better manage his underlying schizophrenia.

As Mr. Johnson's catatonic symptoms resolved, he was gradually reintroduced to group therapy and individual supportive psychotherapy, which helped him address the stressors that may have contributed to the development of catatonia. Additionally, he worked with an occupational therapist to regain his functional abilities and independence in daily activities.

C. Highlight the importance of early intervention

Mr. Johnson's case highlights the importance of early recognition and intervention in catatonia, particularly in patients with co-occurring psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia. His rapid response to benzodiazepine treatment emphasizes the effectiveness of this first-line treatment approach in managing catatonic symptoms. The prompt initiation of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, as well as the optimization of his antipsychotic regimen, allowed Mr. Johnson to recover more quickly and return to his normal daily functioning. This case also underscores the value of a comprehensive treatment approach that addresses both catatonia and the underlying psychiatric condition to promote long-term recovery and reduce the risk of relapse.

Case Study 3: Malignant Catatonia in a Patient with Bipolar Disorder

A. Illustrate various presentations of catatonia

Ms. Thompson, a 28-year-old woman with a history of bipolar disorder, was admitted to the emergency room with rapidly progressing symptoms of fever, tachycardia, hypertension, and altered mental status. Upon examination, she also demonstrated symptoms of catatonia, including immobility, mutism, and posturing. Due to her severe autonomic instability and life-threatening complications, Ms. Thompson was diagnosed with malignant catatonia.

B. Demonstrate successful treatment approaches

Ms. Thompson was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for close monitoring and management of her life-threatening complications. She was started on a trial of lorazepam 2 mg intravenously, which led to a modest improvement in her catatonic symptoms. Given the severity of her condition and the need for rapid symptom resolution, the treatment team decided to proceed with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Ms. Thompson received a series of ECT sessions, which resulted in significant improvement in her catatonic symptoms and stabilization of her autonomic instability. Her mood stabilizer regimen was also optimized to better manage her underlying bipolar disorder.

As Ms. Thompson's catatonic symptoms resolved and her medical condition stabilized, she was gradually reintroduced to group therapy and individual supportive psychotherapy. Additionally, she worked with an occupational therapist to regain her functional abilities and independence in daily activities.

C. Highlight the importance of early intervention

Ms. Thompson's case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and intervention in catatonia, particularly in patients with co-occurring psychiatric conditions like bipolar disorder. Her rapid response to ECT treatment highlights its efficacy and lifesaving potential in severe cases of catatonia, such as malignant catatonia. The prompt initiation of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, as well as the optimization of her mood stabilizer regimen, allowed Ms. Thompson to recover more quickly and return to her normal daily functioning. This case also underscores the value of a comprehensive treatment approach that addresses both catatonia and the underlying psychiatric condition to promote long-term recovery and reduce the risk of relapse.